The compulsive cartography of Tony Curran

— former editor of the Manawatu Standard, Palmerston North, New Zealand

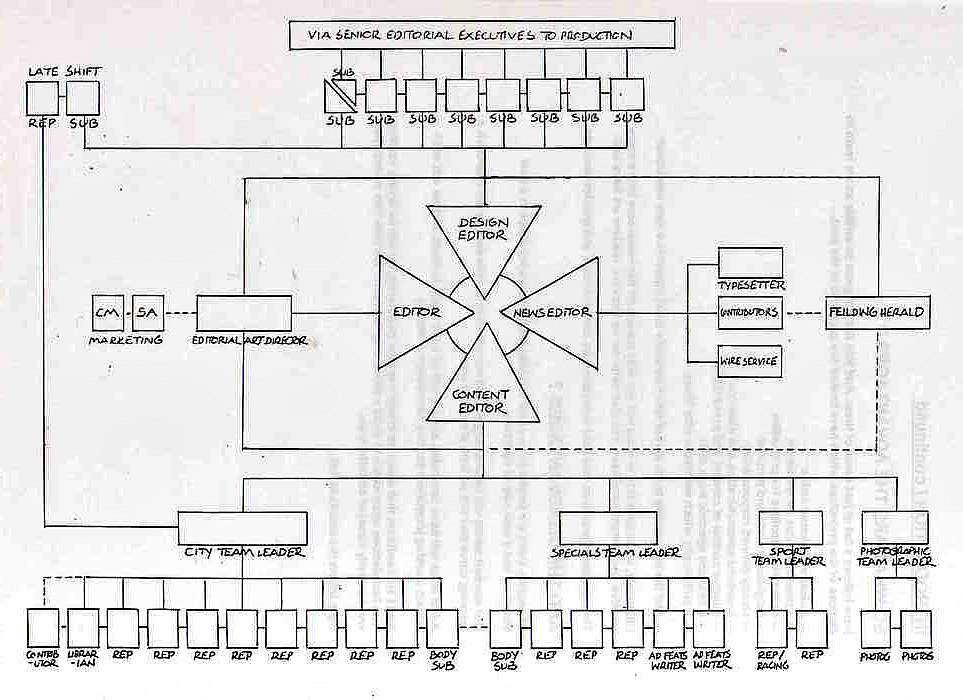

While we journalists did the work, Tony Curran produced diagrams, like the one above, that purported to show paths of communication in an ideal editorial office. It was fantasy. It bore no resemblance to the actual layout of the office in which we produced our newspaper. Click here for "The Blueprint for Our New Newsroom", from which it was taken. Then click here for Curran's first major memo to the editorial staff, dated July 9, 1999. Note its peremptory tone, and the suggestion we see ourselves as "greedy vultures" — rather than as passive recipients of "elitist nonsense". Note, too, that this "nonsense" is described as "in-bred", in what can only be taken as a gratuitous insult to the previous, long-serving editor, John Harvey. Click here for Harvey's comment on Curran.

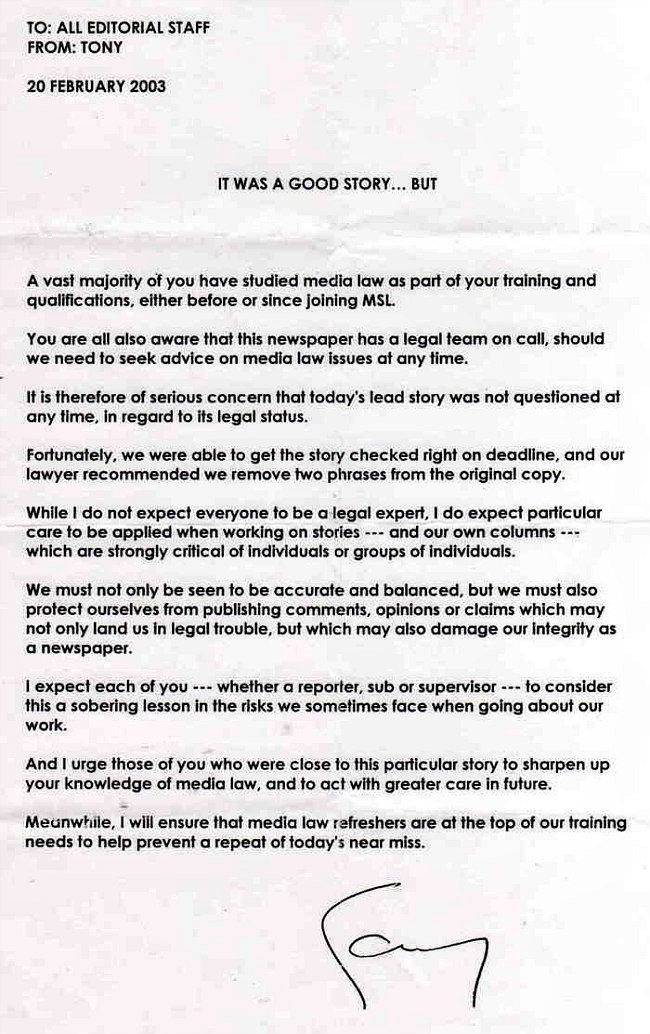

As we approach the 20th anniversary of the appointment of Tony Curran as editor of the Manawatu Standard — now a pitiful tabloid in terminal decline — I am reorganizing my material on his reign, which ran from 1999 to 2003. These items were previously published at Hardcaw — a WordPress blog — under the title "Tony Curran: Wannabe Journalist". Here, I begin by discussing Curran's infamous memo of February 20, 2003 (shown at left, below). I wasn’t in any way involved in the editing of the "good story", but took no pleasure in the discomfiture of those who were. The article is followed by correspondence on the subject of Curran and his career. — Alan Ireland, former subeditor, Manawatu Standard, Palmerston North, December 2018

If Tony Curran had been doing his job as editor, he would have read this important story long before the paper’s deadline.

It wasn’t a major story on Page 13; it wasn’t a major story on Page 3; it was the lead story of the day — at the top of Page 1. And Curran had not, apparently, even given it a glance. What was he doing that morning? Constructing a new copy-flow chart?

As someone observed, Curran always sought to place himself in an unassailable position, so that he could point an accusing finger at subordinates when something went wrong. "In that way, he ends up looking clever, while you end up looking stupid."

To put it another way: Curran’s main aim, during his editorship, was to maximize his control, minimize his responsibility, and hope that, whenever a crisis occurred, no one would notice that his schoolmasterly scoldings were often a smokescreen for an exercise in self-exculpation. But of course, people did notice. And as they became resentful, they increasingly had to be cajoled and coerced into cooperation (or “complicity”, as Curran once said in a memorable misuse of the word).

Hence his constant exhortations, which always carried an undercurrent of menace. Hence the humiliating "motivation workshops", at which we were harangued by outside "experts" with no knowledge of the newspaper industry. Unfortunately, I missed the climax of one of these, which came when the "expert" concerned reportedly slammed the table with his fist, declaring, "Every organization has its saboteurs, and we know who they are!"

I was, however, present at another session that included the screening of a film from Disneyland, featuring Goofy. Incredibly, we were instructed to see Goofy as a role model. Why? Because even when he was off duty, sauntering along a subterranean passage, Goofy still acted "in character". Yes, Goofy was always "on the job" — just as we journos should always be "on the job". After all, intrepid newshounds should never sleep. Nostrils should always be alert to the scent of a "story". With this in mind, Curran issued notebooks and ballpens to all members of the editorial staff, so that, wherever they were, they would be able to record the scintillating goings-on.

In retrospect, it all sounds hilarious. But at the time, it was anything but. I, for one, felt as though as I was back in an English school playground, circa 1950, and that Curran was the presiding bully (complete with north-country accent, which betrayed his cloth-cap origins). And what is a bully? I see him as a leech — a person, usually male, who sucks the lifeblood out of subordinates, never missing an opportunity to increase their "survival anxiety". Of course, there have always been bullies. But today's bully is partly a product of a philosophy that gained ground in the early 1990s, just as the New World Order was finding its feet: that only fear and greed will truly motivate people.

In New Zealand, this philosophy was given substance by the Employment Contracts Act of 1991, which effectively destroyed the union movement and removed the protection from victimization that the employee had previously enjoyed. All this was entirely forseeable at the time the Act was passed. But what could we do? We staged a single protest march around the Square in Palmerston North, and that was that. Rights that were established during centuries of struggle were casually stripped away. Eventually, in America, habeas corpus itself would go — when President Obama signed the National Defense Authorization Act on December 31, 2011. This pernicious Act authorises the indefinite detention, without trial or indictement, of any US citizens designated as enemies by the executive, and effectively takes Western society back to pre-Magna Carta days.

Needless to say, none of this constituted a "story", as far as the mainstream, "Goofyfied" media was concerned. The proverbial Fourth Estate, which should have resisted the destruction of democracy, had long been a party to the process, as a result of its corporatization — otherwise known as "Murdochization".

At the Standard, possibly the most intimidating incident occurred in 2001 — if I remember correctly — when we subeditors were summoned to the abandoned third floor of the building and crammed into a tiny office. After we had sat down, Tony Curran and Mark Stewart stood over us and scolded us in the strongest terms — as though we were a class of naughty schoolchildren. We had the "wrong attitude" and were not pulling our weight in all sorts of ways. It was a profoundly unsettling experience, made worse by the fact that Mark — previously the affable "Father Mark" — did most of the tongue-lashing. A former theology student, he had recently been appointed our superior and had slid a little too easily into the role of Curran's enforcer. Once again, I found myself wondering why I had left a good job in Japan and come to New Zealand, only to be subjected to this sort of treatment. To make matters worse, a new general manager circulated a memo in which he said he was dissatisfied with the "office culture". Culture? What culture? If the atmosphere in the office was sometimes fraught, that was almost entirely the fault of the mentally unhinged person who was in charge at the time. As the Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz observed in one of his experiments, it's the fish with half a brain that leads the shoal.

In considering Curran's peremptory memo on media law, it’s also worth bearing in mind that a lawyer’s opinion is not beyond question. If the paper had approached a different lawyer, it might have received different advice. And in any event, there would have been no guarantee that, after publication of the amended story, there would be no legal consequences.

I hated stories that came to me tagged “THIS HAS BEEN ‘LEGALLED’. DO NOT CHANGE.” Often, on reading such a story, I would find passages that were, even from a legal point of view, not entirely satisfactory. And the English in such passages (which was not, of course, the concern of the legal eagle) was often atrocious. One simply couldn’t let it stand.

It’s also worth noting that some legal principles — strictly adhered to in 1972, when I joined the Standard — were slowly abandoned (and probably completely forgotten) in the following decades. One was that a thief was never to be described as a thief, lest the reader construe, from the wording of the story, that the person was a thief by occupation. The journalist, in his or her defense, could not cite the fact the defendant had been convicted of theft, as a conviction, or even several convictions, did not necessarily mean the person made his living by stealing. (Apparently, someone had once sued a newspaper on this basis, and had won his case.)

Although Curran promised “media law refreshers” to ensure there was no “repeat of today’s near miss”, these never eventuated. Later that year — on an afternoon I will always remember with relish — he received a telephone call from Wellington that abruptly terminated his appointment. The next day, he had gone, leaving bemused company executives wondering what to do with the enormous “imperial” desk he had just had installed in his office.

That the telephone call came as a total surprise was proved by the subsequent publication of an inside-page advertisement inviting members of the public to attend the next “afternoon tea with the editor” — one of those awkward, embarrassing occasions when, after saying he wanted to keep everything “as informal as possible”, Curran would incongruously read a prepared statement to his guests.

In announcing his precipitous departure to the editorial office, he put on a brave face. He was, he said, becoming some sort of roving consulting editor — a position that was “something new” for him. But I think INL — the Standard’s parent company at the time — simply left him to hang out and dry.

Did he sit by the telephone for a couple of days, vainly hoping that it would ring? That someone would be desperate to know whether editorial copy should be routed directly from A to C, or whether it should go via B with input from D? Or that someone still believed that rhetoric, delivered with adolescent enthusiasm and driven home with veiled threats, was all that was needed to turn a lackluster newspaper around?

A couple of weeks later, I saw him in the Square. He strode past me without a flicker of recognition, his mouth as tight as a gin trap.

Click for correspondence on Tony Curran. | Click for musical chairs at the Manawatu Standard.

![]()